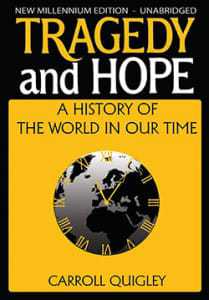

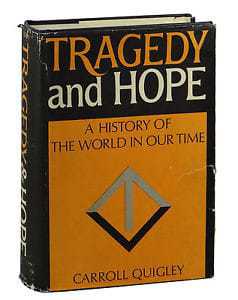

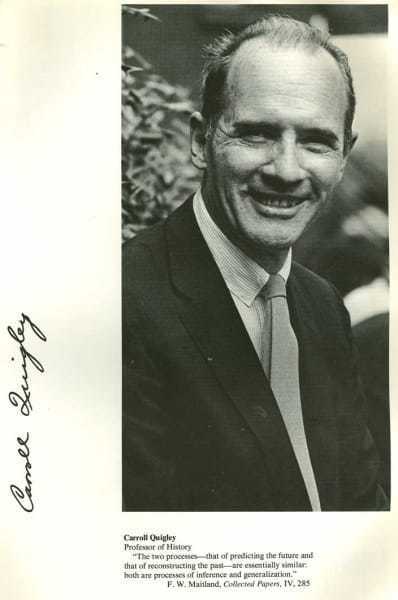

In 1966, Macmillan Company published Tragedy and Hope, a work of exceptional scholarship depicting the history of the world between 1895 and 1965 as seen through the eyes of Quigley. Tragedy and Hope was a commanding work, 20 years in the writing, that added to Quigley’s considerable national reputation as a historian.

Tragedy and Hope reflected Quigley’s feeling that “Western civilization is going down the drain.” That was the tragedy. When the book came out in 1966, Quigley honestly thought the whole show could he salvaged; that was his hope.

During his research, Quigley had noticed that many prominent Englishmen and outstanding British scholars were members of an honorary society:

[…] The powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole, this system was to be controlled in a feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert by secret agreements arrived at in frequent private meetings and conferences. The apex of the system was to be the Bank for International Settlements in Basle, Switzerland, a private bank owned and controlled by the world’s central banks which were themselves private corporations….

It must not be felt that these heads of the world’s chief central banks were themselves substantive powers in world finance. They were not. Rather, they were the technicians and agents of the dominant investment bankers of their own countries, who had raised them up and were perfectly capable of throwing them down. The substantive financial powers of the world were in the hands of these investment bankers (also called ‘international’ or ‘merchant’ bankers) who remained largely behind the scenes in their own unincorporated private banks. These formed a system of international cooperation and national dominance which was more private, more powerful, and more secret than that of their agents in the central banks; this dominance of investment bankers was based on their control over the flows of credit and investment funds in their own countries and throughout the world. They could dominate the financial and industrial systems of their own countries by their influence over the flow of current funds through bank loans, the discount rate, and the re-discounting of commercial debts; they could dominate governments by their own control over current government loans and the play of the international exchanges. Almost all of this power was exercised by the personal influence and prestige of men who had demonstrated their ability in the past to bring off successful financial coups, to keep their word, to remain cool in a crisis, and to share their winning opportunities with their associates.

At the time, Quigley had no way of knowing he had just written his own ticket to a curious kind of fame. He was about to become a reluctant hero to Americans who believe the world is neatly controlled by a clique of international bankers and their cronies. Quigley learned of the country’s great appetite for believing a grand conspiracy causes everything from big wars to bad weather.

Tragedy and Hope is not all juicy conspiratorial material. Most of it is straight diplomatic, political, and economic history. All of it is brilliant. His insights on such otherwise ignored (and crucially important) topics as Japanese military history and its relation to family dynasties is fascinating. But it did not gain its notoriety or its sales because of these non-conspiratorial insights.