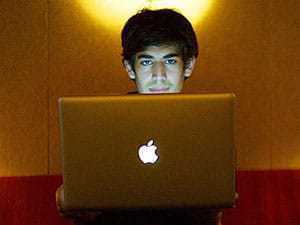

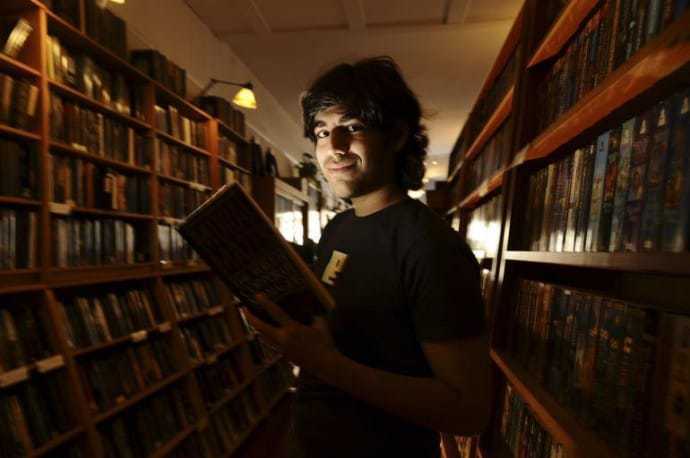

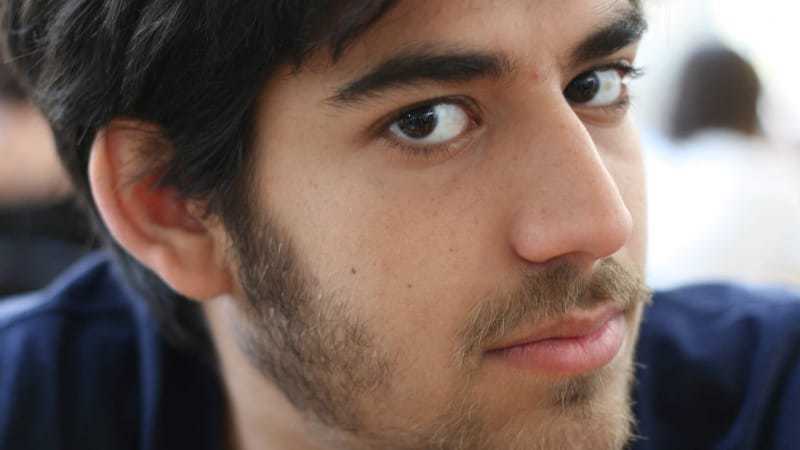

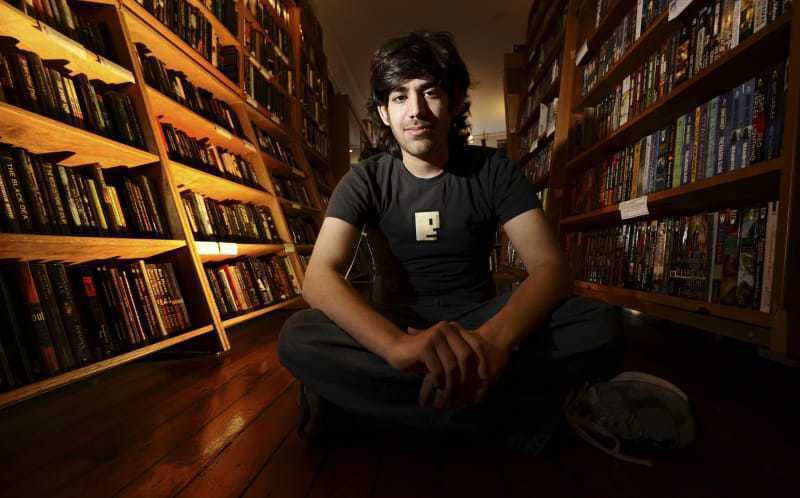

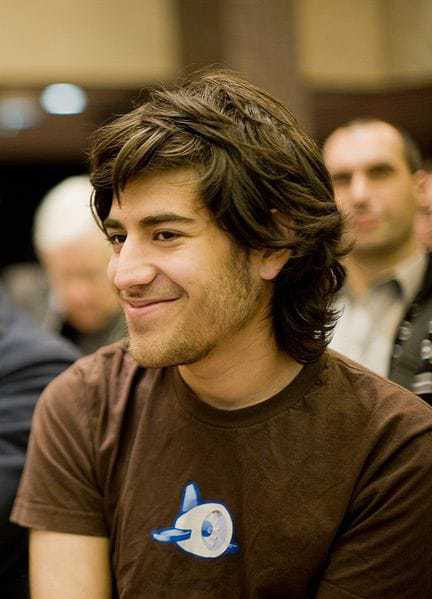

Aaron Swartz

It’s taken me two years to write about this experience, not without reason. One terrifying side effect of learning the world isn't the way you think is that it leaves you all alone. And when you try to describe your new worldview to people, it either comes out sounding unsurprising (“yeah, sure, everyone knows the media’s got problems”) or like pure lunacy and people slowly back away. Ever since then, I've realized that I need to spend my life working to fix the shocking brokenness I'd discovered. And the best way to do that, I concluded, was to try to share what I'd discovered with others. I couldn't just tell them it straight out, I knew, so I had to provide the hard evidence. So I started working on a book to do just that...

Aaron Swartz was born on November 8, 1986, in Chicago. Precocious from the start, Swartz taught himself to read when he was only three, and when he was 12, Swartz created Info Network, a user-generated encyclopedia, which Swartz later likened to an early version of Wikipedia.

Info Network landed Swartz in the finals for the ArsDigita Prize, and he also was invited to join the RDF Core Working Group of W3C (World Wide Web Consortium), a group assembled to help the Web evolve.

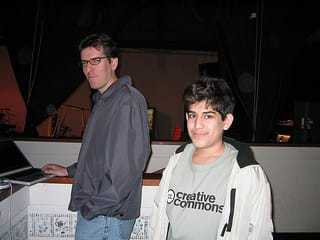

RSS & Creative Commons

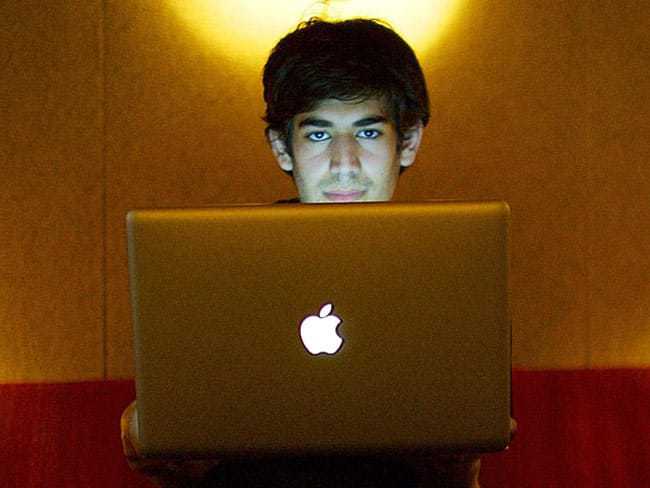

Swartz’s next steps were co-authoring news aggregator RSS 1.0 (which went on to become the industry standard) and moving to San Francisco to write code for Creative Commons, a public domain watchdog group. He then headed to California to study sociology at Stanford University. At Stanford, he downloaded law review articles from the Westlaw database and used the data to write an important paper about the connection between research funders and biased results. However, he left academia after only a year, taking a leave of absence to join Y Combinator, an incubator for up-and-coming Internet talent.

Also around this time, Swartz’s new project, Infogami, merged with Reddit.com, making Swartz a co-founder of the resulting company. Reddit had millions of visitors per month when Condé Nast bought it a year later (2006).

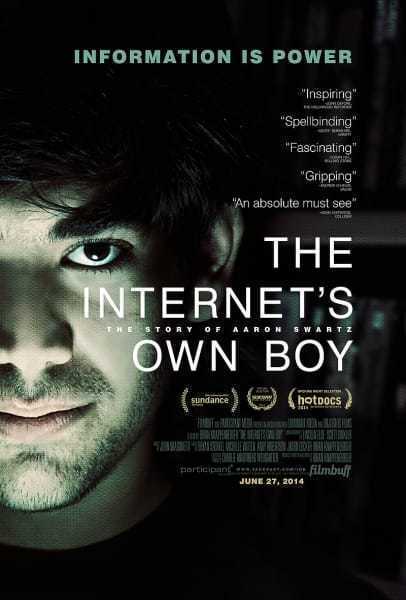

In 2008 Swartz wrote “Guerilla Open Access Manifesto,” which was an argument against information being hoarded and controlled by any particular group. The document ended with a demand that information be freely available and grabbed forcibly, if need be: “We need to take information, wherever it is stored, [and] make our copies and share them with the world.”

Felony Charges

That fall, Swartz decided to take on PACER, a system that charged users to download court documents. Through an algorithm he wrote, Swartz downloaded 19,865,160 pages of text from the database. By the spring of 2009, FBI agents were at Swartz’s door, questioning him about the downloads. The investigation was dropped, but a year later Swartz began downloading academic articles from the JSTOR archive at MIT, ending up with around 5 million documents. Swartz’s motivation for downloading the articles was never fully determined, however, friends and colleagues believe his intention was either to upload them to the Internet to share them with the public or analyze them to uncover corruption in the funding of climate change research.

After launching activist group Progressive Change Campaign Committee and later Demand Progress, in January 2011, Swartz was detained in Cambridge, Mass. by police and Secret Service agents. Since his activities in PACER, the government had been watching, and by July 2011, Swartz was facing multiple counts of computer and wire fraud, charges that could have resulted in 35 years in federal prison.

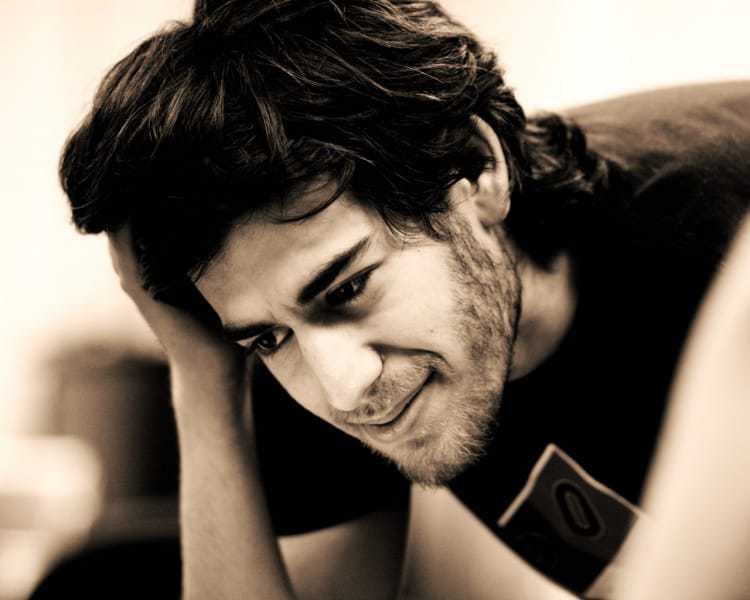

Over the next year and a half, the government added multiple counts to the original charges, eventually offering him a plea deal, however, Swartz refused it asserting his innocence. Swartz was left feeling more and more trapped, fearful of the federal charges and their implications.

Tragic Death

By January 2013, Swartz was in a depression, and his demeanor was making those around him nervous. On the night of January 11, friends’ fears were realized when they found Swartz dead, hanging by a belt in his Crown Heights, Brooklyn, apartment.

His family released a statement after his death which included this statement: “Aaron’s death is not simply a personal tragedy. It is the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach. Decisions made by officials in the Massachusetts US attorney’s office and at MIT contributed to his death.’’

Since Swartz’s suicide, congressional investigations have been launched into the Justice Department’s prosecution of Swartz, and a bill called “Aaron’s Law” has been introduced to amend the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act to rein in such prosecution in the future.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.