Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Bulwer-Lytton's most famous quotation, ``the pen is mightier than the sword``, is from his play Richelieu where it appears in the line beneath the rule of men entirely great, ``the pen is mightier than the sword``. In addition, he gave the world the memorable phrase ``pursuit of the almighty dollar`` from his novel The Coming Race. He is also credited with ``the great unwashed``. He used this rather disparaging term in his 1830 novel Paul Clifford. He is certainly a man who bathes and ‘lives cleanly’, (two especial charges preferred against him by Messrs. the Great Unwashed. — Happy is the man who hath never known what it is to taste of fame; to have it is a purgatory, to want it is a hell.

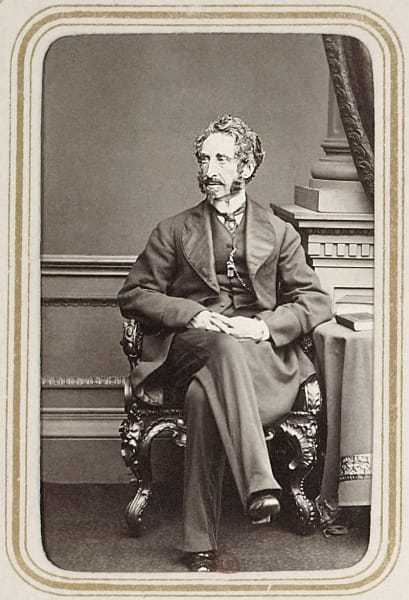

Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton PC (25 May 1803 – 18 January 1873), was an English novelist, poet, playwright, and politician. He was immensely popular with the reading public and wrote a stream of bestselling novels which earned him a considerable fortune. He coined the phrases “the great unwashed”, “pursuit of the almighty dollar”, “the pen is mightier than the sword”, “dweller on the threshold”, as well as the well-known opening line “It was a dark and stormy night”.

Life

Bulwer-Lytton was born on 25 May 1803 to General William Earle Bulwer of Heydon Hall and Wood Dalling, Norfolk and Elizabeth Barbara Lytton, daughter of Richard Warburton Lytton of Knebworth, Hertfordshire. He had two elder brothers, William Earle Lytton Bulwer (1799–1877) and Henry (1801–1872), later Lord Dalling and Bulwer.

When Edward was four his father died and his mother moved to London. He was a delicate, neurotic child and was discontented at a number of boarding schools. But he was precocious and Mr Wallington at Baling encouraged him to publish, at the age of fifteen, an immature work, Ishmael and Other Poems.

In 1822 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he met John Auldjo, but shortly afterwards moved to Trinity Hall. In 1825 he won the Chancellor’s Gold Medal for English verse. In the following year he took his B.A. degree and printed, for private circulation, a small volume of poems, Weeds and Wild Flowers.

He purchased a commission in the army, but sold it without serving.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton. His Harold, the Last of the Saxons (1848) was the source for Verdi’s opera Aroldo

In August 1827, against his mother’s wishes, he married Rosina Doyle Wheeler (1802–1882), a famous Irish beauty. When they married his mother withdrew his allowance and he was forced to work for a living. They had two children, Lady Emily Elizabeth Bulwer-Lytton (1828–1848), and (Edward) Robert Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton (1831–1891) who became Governor-General and Viceroy of British India (1876–1880).

His writing and political work strained their marriage while his infidelity embittered Rosina; in 1833 they separated acrimoniously and in 1836 the separation became legal. Three years later, Rosina published Cheveley, or the Man of Honour (1839), a near-libellous fiction bitterly satirising her husband’s alleged hypocrisy.

In June 1858, when her husband was standing as parliamentary candidate for Hertfordshire, she indignantly denounced him at the hustings. He retaliated by threatening her publishers, withholding her allowance, and denying access to the children. Finally he had her committed to a mental asylum. But, after a public outcry she was released a few weeks later. This incident was chronicled in her memoir, A Blighted Life (1880). For years she continued her attacks upon her husband’s character.

The death of Bulwer-Lytton’s mother in 1843 greatly saddened him. His own “exhaustion of toil and study had been completed by great anxiety and grief”, and by “about the January of 1844, I was thoroughly shattered”. In his mother’s room, Bulwer-Lytton “had inscribed above the mantelpiece a request that future generations preserve the room as his beloved mother had used it”; it remains essentially unchanged to this day.

On 20 February 1844, in accordance with his mother’s will, he changed his surname from ‘Bulwer’ to ‘Bulwer-Lytton’ and assumed the arms of Lytton by royal licence. His widowed mother had done the same in 1811. But, his brothers remained plain ‘Bulwer’.

By chance he encountered a copy of “Captain Claridge’s work on the “Water Cure”, as practised by Priessnitz, at Graefenberg”, and “making allowances for certain exaggerations therein”, pondered the option of travelling to Graefenberg, but preferred to find something closer to home, with access to his own doctors in case of failure: “I who scarcely lived through a day without leech or potion!”.

After reading a pamphlet by Doctor James Wilson, who operated a hydropathic establishment with James Manby Gully at Malvern, he stayed there for “some nine or ten weeks”, after which he “continued the system some seven weeks longer under Doctor Weiss, at Petersham”, then again at “Doctor Schmidt’s magnificent hydropathic establishment at Boppart” (at the former Marienberg Convent at Boppard), after developing a cold and fever upon his return home.

When King Otto of Greece abdicated in 1862, he was offered the crown of Greece, which he declined.

In 1866 Bulwer-Lytton was raised to the peerage as Baron Lytton.

The English Rosicrucian society, founded in 1867 by Robert Wentworth Little, claimed Bulwer-Lytton as their ‘Grand Patron’, but he wrote to the society complaining that he was ‘extremely surprised’ by their use of the title, as he had ‘never sanctioned such’. Nevertheless, a number of esoteric groups have continued to claim Bulwer-Lytton as their own, chiefly because some of his writings—such as the 1842 book Zanoni—have included Rosicrucian and other esoteric notions. According to the Fulham Football Club, he once resided in the original Craven Cottage, today the site of their stadium.

Bulwer-Lytton had long suffered with a disease of the ear and for the last two or three years of his life he lived in Torquay nursing his health. Following an operation to cure deafness, an abscess formed in his ear and burst; he endured intense pain for a week and died at 2am on 18 January 1873 just short of his 70th birthday. The cause of death was not clear but it was thought that the infection had affected his brain and caused a fit. Rosina outlived him by nine years. Against his wishes, Bulwer-Lytton was honoured with a burial in Westminster Abbey.

His unfinished history Athens: Its Rise and Fall was published posthumously.

Career

Bulwer-Lytton began his career as a follower of Jeremy Bentham. In 1831 he was elected member for St Ives in Cornwall, after which he was returned for Lincoln in 1832, and sat in Parliament for that city for nine years. He spoke in favour of the Reform Bill, and took the leading part in securing the reduction, after vainly essaying the repeal, of the newspaper stamp duties. His influence was perhaps most keenly felt when, on the Whigs’ dismissal from office in 1834, he issued a pamphlet entitled A Letter to a Late Cabinet Minister on the Crisis. Lord Melbourne, then Prime Minister, offered him a lordship of the admiralty, which he declined as likely to interfere with his activity as an author.

In 1841, he left Parliament and didn’t return to politics until 1852; this time, having differed from the policy of Lord John Russell over the Corn Laws, he stood for Hertfordshire as a Conservative. Lord Lytton held that seat until 1866, when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Lytton of Knebworth in the County of Hertford. In 1858 he entered Lord Derby’s government as Secretary of State for the Colonies, thus serving alongside his old friend Disraeli. In the House of Lords he was comparatively inactive. He took a proprietary interest in the development of the Crown Colony of British Columbia and wrote with great passion to the Royal Engineers upon assigning them their duties there. The former HBC Fort Dallas at Camchin, the confluence of the Thompson and Fraser Rivers, was renamed in his honour by Governor Sir James Douglas in 1858 as Lytton, British Columbia.

Literary works

Bulwer-Lytton’s literary career began in 1820—with the publication of a book of poems—and spanned much of the nineteenth century. He wrote in a variety of genres, including historical fiction, mystery, romance, the occult, and science fiction. He financed his extravagant life with a varied and prolific literary output, sometimes publishing anonymously.

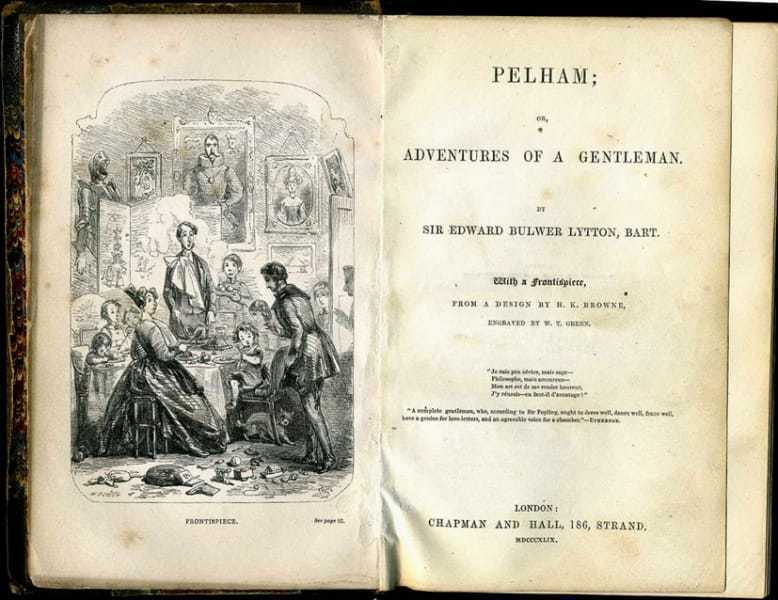

1849 printing of Pelham with Hablot K. Browne (Phiz) frontispiece: Pelham’s electioneering visit to the Revd. Combermere St Quintin, who is surprised at dinner with his family.

In 1828 Pelham brought him public acclaim and established his reputation as a wit and dandy. The book also made a significant contribution in the changing of men’s fashion. Prior to the novel, evening wear for men could be of any colour, but the upper-class quickly adopted the habit of using black evening wear only, a habit that is still dominant, just as the characters in Pelham. Its intricate plot and humorous, intimate portrayal of pre-Victorian dandyism kept gossips busy trying to associate public figures with characters in the book. Pelham resembled Benjamin Disraeli’s recent first novel Vivian Grey (1827).

Bulwer-Lytton admired Benjamin’s father, Isaac D’Israeli, himself a noted author. They began corresponding in the late 1820s and met for the first time in March 1830, when Isaac D’Israeli dined at Bulwer-Lytton’s house. (Also present that evening were Charles Pelham Villiers and Alexander Cockburn. The young Villiers was to have a long parliamentary career, while Cockburn became Lord Chief Justice of England in 1859.)

Bulwer-Lytton reached the height of his popularity with the publication of Godolphin (1833). This was followed by The Pilgrims of the Rhine (1834), The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), Rienzi, Last of the Roman Tribunes (1835), and Harold, the Last of the Saxons (1848). The Last Days of Pompeii was inspired by Karl Briullov’s painting, The Last Day of Pompeii, which Bulwer-Lytton saw in Milan.

He also wrote the horror story “The Haunted and the Haunters” or “The House and the Brain” (1859). Another novel dealing with a supernatural theme was A Strange Story (1862), which was an influence on Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Bulwer-Lyton penned many other works, including The Coming Race or Vril: The Power of the Coming Race (1871), which drew heavily on his interest in the occult and contributed to the birth of the science fiction genre. Its story of a subterranean race waiting to reclaim the surface of the Earth is an early science fiction theme. The book popularised the Hollow Earth theory and may have inspired Nazi mysticism. His term “vril” lent its name to Bovril meat extract. Adopted by theosophists and occultists since the 1870s, “vril” would develop into a major esoteric topic, and eventually become closely associated with the ideas of an esoteric neo-Nazism after 1945.

His play, Money (1840), was first produced at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, London, on 8 December 1840. The first American production was at the Old Park Theater in New York on 1 February 1841. Subsequent productions include the Prince of Wales’s Theatre’s in 1872 and it was also the inaugural play at the new California Theatre in San Francisco in 1869.

Among Bulwer-Lytton’s lesser-known contributions to literature is that he convinced Charles Dickens to revise the ending of Great Expectations to make it more palatable to the reading public, as in the original version of the novel, Pip and Estella do not get together.

Legacy

Bulwer-Lytton’s most famous quotation, “the pen is mightier than the sword”, is from his play Richelieu where it appears in the line “beneath the rule of men entirely great, the pen is mightier than the sword.” In addition, he gave the world the memorable phrase “pursuit of the almighty dollar” from his novel The Coming Race. He is also credited with “the great unwashed”. He used this rather disparaging term in his 1830 novel Paul Clifford: “He is certainly a man who bathes and ‘lives cleanly’”, (two especial charges preferred against him by Messrs. the Great Unwashed).

The Last Days of Pompeii has been cited as the first source, but inspection of the original text shows this to be wrong. However, the term “the Unwashed” with the same meaning, appears in The Parisians: “He says that Paris has grown so dirty since 4 September, that it is only fit for the feet of the Unwashed.” The Parisians, though, was not published until 1872, while William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel Pendennis (1850) uses the phrase ironically, implying it was already established. The Oxford English Dictionary refers to “Messrs. the Great Unwashed” in Lytton’s Paul Clifford (1830), as the earliest instance.

Bulwer-Lytton is also credited with the appellation for the Germans “Das Volk der Dichter und Denker”, that is, the people of poets and thinkers